A groundbreaking study has unveiled a fascinating link between the evolution of the human brain and its aging process, shedding light on how our cognitive abilities may come with unexpected costs. Researchers have developed a novel framework for comparing brain structures across different species, revealing that the expansive growth of the human brain, especially in regions responsible for higher cognitive functions, comes with an increased vulnerability to age-related decline.

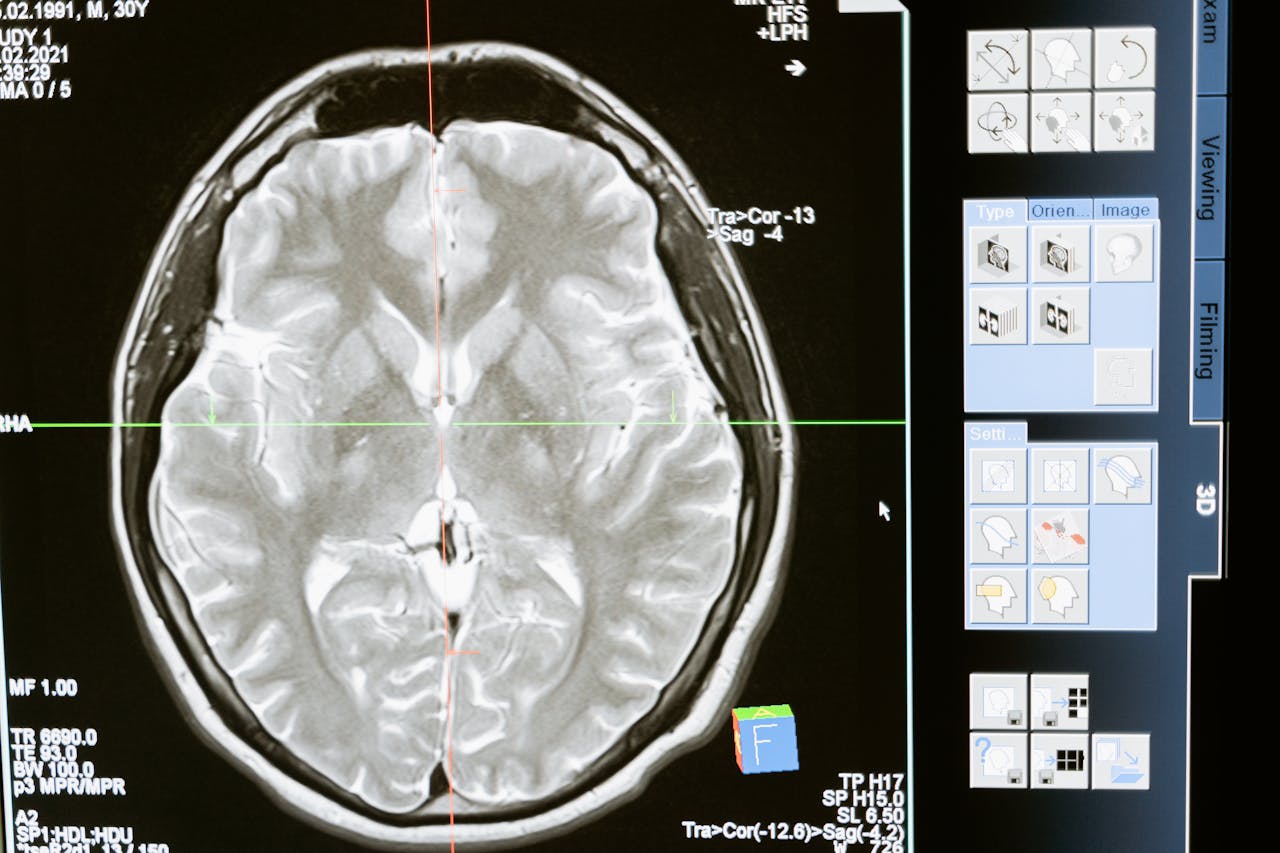

The study, which involved a comparative analysis of brain scans from humans, chimpanzees, and other primates, employed a technique known as Orthogonal Procrustes Non-negative Matrix Factorization (OPNMF). This method helps to identify and compare the organization of brain structures by clustering them into distinct regions based on their spatial and anatomical features.

The findings are striking. Humans have experienced significant expansion in their prefrontal cortex (PFC), a brain region associated with complex cognitive functions like executive control, working memory, and language. This expansion is more pronounced compared to our closest relatives, the chimpanzees, and other primates like baboons and macaques. However, this growth comes with a downside: the human brain’s greater expansion is linked to a marked decline in grey matter (GM) volume with age.

In contrast, the study found that chimpanzees do not exhibit a similar relationship between brain expansion and aging. The grey matter decline in chimpanzees was present but did not correlate with the expansion of brain regions as it does in humans. This suggests that while chimpanzees’ brains have also evolved, their structural changes do not lead to the same degree of age-related vulnerability as seen in humans.

One of the key insights from this research is the concept of “expansion at a cost.” As the human brain expanded, particularly in areas such as the PFC, it became more susceptible to aging-related decline. This is not observed in the same way in chimpanzees, where brain expansion does not correlate with age-related GM reduction to the same extent.

The study’s use of OPNMF revealed that both humans and chimpanzees have similar basic brain organization patterns, such as symmetrical hemispheres and recognizable macroanatomical structures. However, the human brain shows more pronounced expansion in regions linked to higher-order cognitive functions. This extensive growth in regions like the frontal and parietal lobes, while beneficial for complex cognitive tasks, seems to make these areas more prone to degeneration as we age.

The research highlights that human brains have a greater “neuropil fraction” — the space around neurons filled with dendrites and axonal connections. This increased neuropil, which supports the dense network of connections required for advanced cognitive processes, may contribute to the observed decline in grey matter with aging. Essentially, the more complex and expansive our brain networks become, the more they seem to be affected by the aging process.

While these findings provide valuable insights into the evolutionary trade-offs of brain expansion, the study also notes some limitations. For instance, the research was based on cross-sectional data, and future longitudinal studies could offer a clearer picture of how brain aging progresses over time. Additionally, the study’s sample included a skewed gender ratio among chimpanzees, which may have influenced the results.

Overall, this research deepens our understanding of how the human brain’s evolutionary trajectory, particularly its expansion, interacts with the aging process. It suggests that the very advancements that have allowed humans to develop complex cognitive functions may also render our brains more vulnerable to age-related changes.

Citation(s):

Vickery, S., Patil, K. R., Dahnke, R., Hopkins, W. D., Sherwood, C. C., Caspers, S., Eickhoff, S. B., & Hoffstaedter, F. (2024). The uniqueness of human vulnerability to brain aging in great ape evolution. Science Advances, 10(35), Article eado2733. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ado2733